Little Snow White: The Mirror Made Her Do It

In the Grimms’ Little Snow White, the so-called Evil Queen isn’t much of a villain—her mirror is. Fr

You, like many people, have once upon a time believed a terrible lie. The lie is this: Fairy tales are for bedtime stories, and one day we have to grow up and start reading something else. There’s nothing wrong with reading something else, but by Basile, this lie is up with the best of them.

So, you, like many people, may hear that this lie is a lie and ask: Why dedicate so much time and effort to make a podcast about fairy tales?

You can read the short blurb in our FAQ, but if you want the long version, it starts with redefining the lie that we’re all told about what fairy tales are and who they are for.

Short answer: There is no definition.

Fairy tales are often said to be short stories that have been passed down orally, so they have no direct author. It’s said that they belong to the folklore genre and typically include magic creatures, items, or enchantments. That these stories all need a moral or a lesson to be learned, that they present a clear contrast between good and evil, and that they are tied to a generic setting where they could realistically have happened at any time and at any place.

But, you see, if we went by that strict definition, that would mean these wouldn’t be fairy tales:

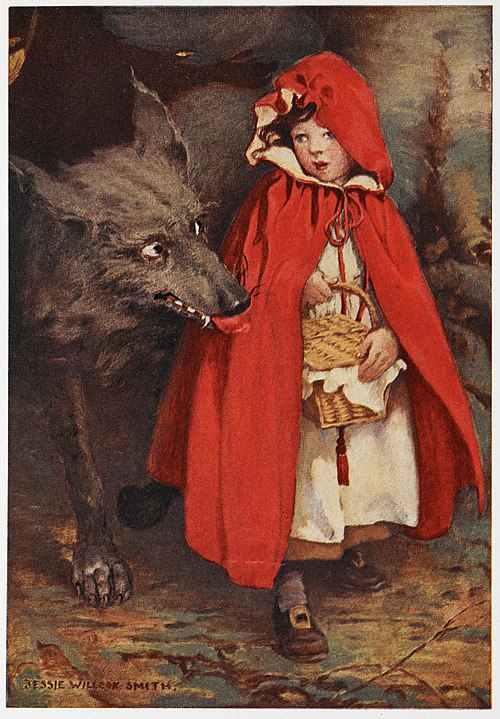

And don’t forget, if an animal talks, like in Chicken Little, The Musicians of Bremen, (or Little Red Riding Hood!), it’s not a fairy tale, it’s a fable.

But I consider all of these to be fairy tales. Even* Peter Pan* could be argued to be a fairy tale. I think they are, and that’s the point.

I said above, “there is no definition” for a fairy tale, it’s up to a listener’s definition, but here is mine, even though you never asked:

Some are short, some are epic. Some are oozing with magic, others are realistically horrific for no reason at all. Some have morals, some have talking cats, some are old, and some are being written as you read. The days of fairy tales aren’t past as long as imagination is alive and well. And the old ones survive to now not because they fit into neat boxes of “What makes a fairy tale just that?” but because we love to tell them, read them, and hear them all over again.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. That doesn’t answer the question “Why Fairy Tales?” does it? Well, let’s talk about that.

Another short answer for you: We started this podcast because we learned how much fairy tales matter. If you look at just one type of fairy tale that can be defined, *Oral Fairy Tales*, these are the ones that don’t have an author. Their history can’t be tracked; they’ve been heard by generations of ears, each hearing the tale differently as the storytellers inflect part of who they are into the story. They’re a collective creation shaped by the voices and ears of every person who’d told or heard them before.

Oral Fairy Tales represent the voices of ordinary people. Unlike history, which is often written by the victors or those in power, these tales come from the hearts of folks like us. They reveal what life was like for those who didn’t have the luxury of literacy or the rarity called reading.

In fairy tales, we see true humanity in what people feared, what they hoped for, and how they understood this world. It’s pure, unfiltered history and evidence of what it really means to be human.

With this, I’ve found fairy tales as an incredible link to the past—a way to connect us to the very first storytellers and the timeless human nature of sharing tales.

When I first started learning about fairy tales, I could be found glued to a page or a screen in perfect silence. Reading to my own mind and discovering wonderous false histories that never happened—yet became true exactly because of that. There’s such depth and discussion to be had in these stories, and yet I was alone.

In the words of Seumas MacManus, “He would wish that this world might hear of the wonderful happenings with our ears, and see them with our eyes.”

You likely have never heard of Seumas MacManus, but as one of Irish descent, MacManus is a personal hero of mine, and I aim to be a seanchaí myself.

You see, these stories deserve to be heard. Those storytellers, some long gone and near-forgotten, deserve a voice. In a world increasingly dominated by technology and artificial intelligence, the art of being human—the art of imperfection—is becoming a rarity, and yet oral storytelling is made more possible than when Jacob (probably) said, “We should really start writing this down, Wilhelm.”

Podcasts like Once Upon a Podcast are part of this revival, bringing these ancient tales back to life in a modern form. We aim to give voices again to Basile, d’Aulnoy, Grimm, Andersen, MacManus, Fillmore, and the many, many more.

Fairy tales are a way we can reach into the past. They bridge cultures, connect generations, and offer a glimpse into the fears and hopes of people long ago and today. They’re history reflected through storytelling and the timeless nature of human imagination. That’s why it’s Fairy Tales. There’s no better way to remember, to celebrate, and to keep the stories misbehaving.

Journey deeper into our collection of weekly episodes where folklore meets analysis and chaos reigns supreme in the most delightful way.

Continue your journey through our collection of fairy tale deep dives and folklore insights.

In the Grimms’ Little Snow White, the so-called Evil Queen isn’t much of a villain—her mirror is. Fr

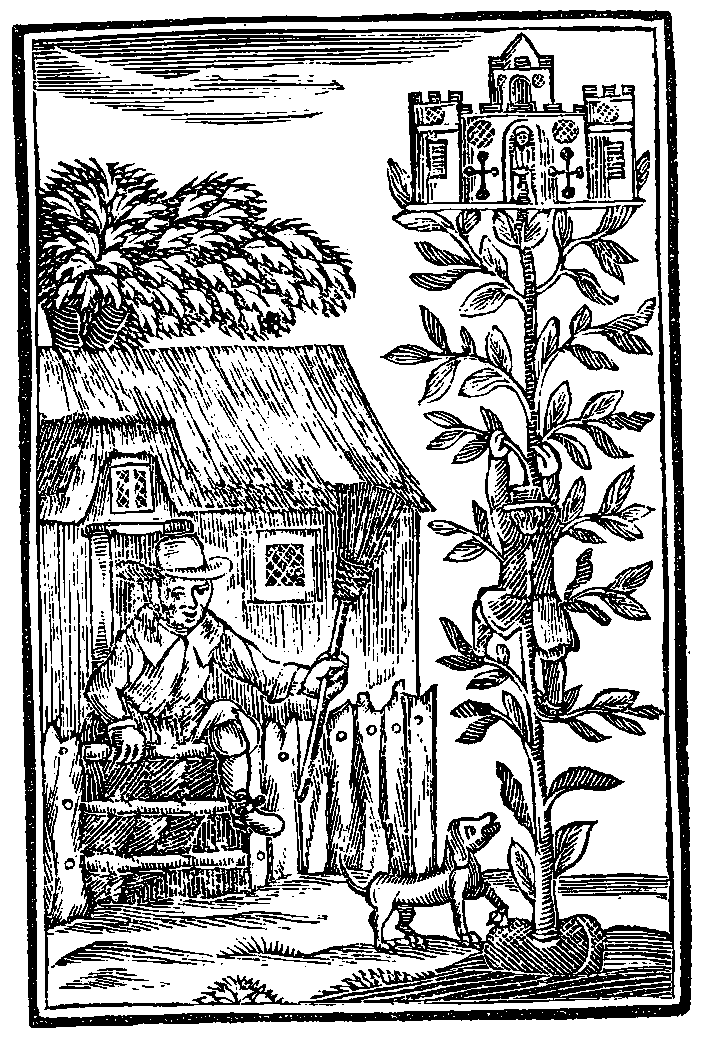

Explore the curious origins of The Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean (1734), the earlie